Colchester’s Roots in Agriculture: Then and Now

Colchester’s roots in agriculture began before its establishment by European settlers from Wethersfield in 1698. Granted by the General Court of the Colony of Connecticut in Hartford, the original “new plantation” was in a large tract of land known as Jeremiah’s Farms, or Twenty Mile River, “on the road to New London,” a location north of the present Town Green. Legend has it that the original settlement was where the Hamilton Wallis Farm stood, now Chanticlair Golf Club.

Colchester’s roots in agriculture began before its establishment by European settlers from Wethersfield in 1698. Granted by the General Court of the Colony of Connecticut in Hartford, the original “new plantation” was in a large tract of land known as Jeremiah’s Farms, or Twenty Mile River, “on the road to New London,” a location north of the present Town Green. Legend has it that the original settlement was where the Hamilton Wallis Farm stood, now Chanticlair Golf Club.

The original deed to the land was purchased by Nathaniel Foote from Owaneco, Sachem of the Mohegan Indians, to establish a settlement. Nathaniel’s grandfather, having emigrated to this country, had previously been a resident of Colchester, England, hence the town’s name. Early settler’s lives typically centered around religious life, and in 1703 Colchester received permission from the Colony’s General Assembly to organize as an ecclesiastical society, and in 1706 hiring the Reverend John Bulkeley as their first minister.

The Town of Colchester contains the villages of Westchester and North Westchester as well as the Golden Hill Paugussett Indian Nation reservation. Prior to the arrival of English settlers, Colchester’s indigenous people cultivated maize (corn), beans, squash, sunflowers and Jerusalem artichokes. English settlers were taught growing techniques from the Native Americans and, as was their habit, the settlers cleared large areas of land for crops and livestock grazing.

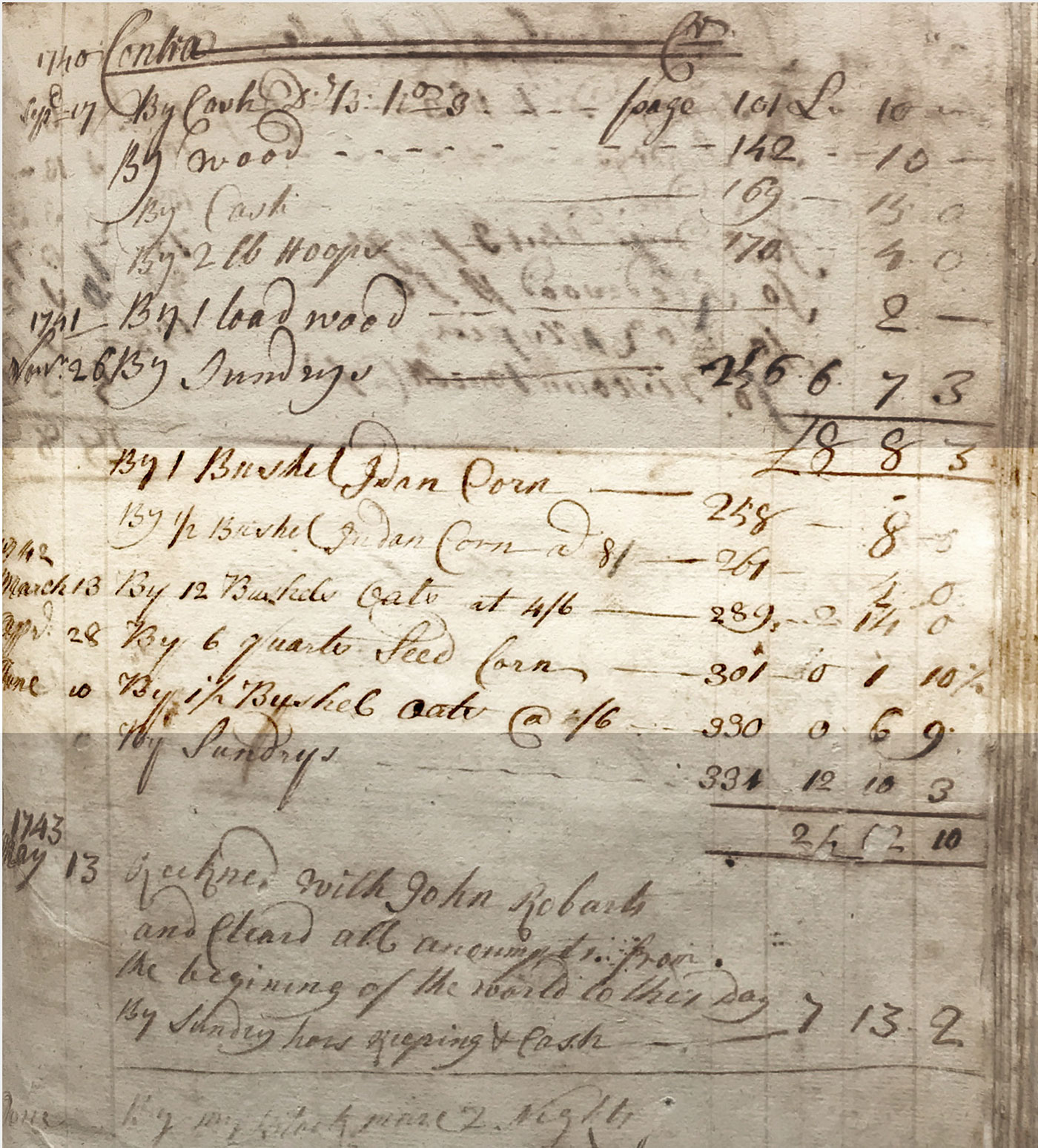

An account book of Joseph Stewart’s general store (seen below) in Colchester, illustrates the agricultural, household and personal goods exchanged during 1740-1743. In Colonial America, currency was scarce and barter was commonly used for exchanging goods and services. As seen in the account book, farmers would exchange Indian Corn, Rye or Bushels of wheat for beaver hats, brimstone or brooms. A general store often operated as a post office and a rudimentary bank, collecting debts owed and recording credit paid in their ledger.

By the late 1700s, agriculture was Colchester’s primary livelihood with many large, thriving farms. Crops and livestock from local farms were sold at ports in New London and Norwich.

In 1776, Colonel Henry Champion, whose home still stands in Westchester, a farmer and member of the 25th Regiment serving in the Revolutionary War, was appointed Commissary General for the military troops. In the spring of 1780, after a long hungry winter fighting in Morristown, New Jersey, General George Washington sought assistance from his Commissary General. In response, Colonel Champion supplied provisions by driving his own livestock to New Jersey to feed Washington’s starving troops.

Pierpont Bacon, who famously left a sum of $35,000 for the founding of Bacon Academy, gained wealth by operating several large farms. Bacon was able to manage large farms partly because he kept slaves. In 1775, 5% of the population of Colchester were enslaved African Americans. A 1790 inventory of slave owners in Connecticut, lists Pierpont Bacon’s ownership of six slaves. Upon his death in 1803, Pierpont Bacon emancipated his slaves, leaving a forty-four-acre farm with a house and barn, to his slave, Jenny, and her son Cato. Cato subsequently rented the farm to a neighboring white farmer, but maintaining use of his house.

In early 19th-century Connecticut, 90% of the inhabitants made most of their living from farming. Even citizens with professions, lawyers, physicians, etc., farmed in order to feed themselves and their families. Luxury goods, such as coffee, tea or sugar, were acquired through barter or trade. Evidence of a trade credit and deficit system can be seen in the ledger of Colchester farmer, Joseph D. Kellogg. Individuals worked the farm, or earned credit through “washing and ironing” in trade for commodities such as butter, or pork. Farmers were resourceful, building, repairing, and conserving wherever was needed. By the middle of the century, support for farmers emerged through “Farmer’s Clubs”, and agricultural societies, such as the New London Agricultural Society, where local resident, Charles Bailey was a member. A national Grange organization was founded in 1867. Officially titled the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, The Grange, was organized to promote a social and educational environment for farmers and their families.

As the century wore on, industrial expansion slowly began to impact the local economy and by 1893, Colchester had three tanneries, an iron works, a woolen mill, a hatter, a wheel and carriage factory, a paper mill, a creamery and a canning company. Many of these businesses were an outgrowth of the strength of agriculture in the community. In 1896, the Colchester Creamery posted a comprehensive list of regulations regarding the quality of their collective product by expecting “the hearty cooperation of every patron and rigid adherence to the following rules,” with a long list of provisions for cleanliness, and high quality.

The Hayward Rubber Company, established in 1847 by Nathaniel Hayward, had a huge impact on the Colchester community, providing industrial employment and contributing to the population and economic growth. The factory attracted a large labor force, many of them immigrants, including workers of Irish, German and Jewish heritage, bringing rapid growth to Colchester. In 1893 the Hayward Rubber Company abruptly closed creating a local economic bust. Land was now cheap and abundant.

Agri-business, however, was given a boost in early 1900 through support for Jewish immigrant resettlement by the Baron de Hirsch Fund of New York (see The Impact of Baron Maurice de Hirsch panel). Immigrants flocked to Colchester in search of a better life and introducing the local community to diverse cultures and ultimately launching a tourism industry. Frustrated with the local rocky soil, the refugees turned to dairy and poultry farming and supplementing their income by taking in boarders from New York and other nearby cities. The practice became popular and soon Colchester became a tourist destination sometimes known as the “Catskills of Connecticut.”

Photographs of immigrant farmers were captured in 1940 by Farm Security Administration photographer Jack Delano. Delano recorded the plight of the part-time farmer; the farmers who worked part-time in local manufacturing or took in boarders to supplement their income. Abraham Lapping is captured in November 1940, carrying pails in his dairy barn. He and his wife hosted boarders, while operating both a dairy and a chicken farm.

In addition to Jewish immigrants, ethnic groups migrating to the region included Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Irish, Armenians, and French-Canadians. The diverse population of immigrants embracing opportunity operated primarily dairy and poultry farms, many while also working in local clothing factories and retail stores. The family of Constantino DeNora, emigrated from Italy to New York, ultimately moving to Colchester to operate a multi-generational egg farm. A Frank Delano photograph shows the DeNora family gathered in their kitchen.

During the Great Depression, 1929-1939, approximately 750,000 farms nationwide were lost to bankruptcy. In 1933, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, a farm-relief bill, was passed to help farmers retain their property. With the onset of the depression, the resorts gradually closed. Multi-generational dairy and egg farming continued through the 1950s and 1960s.

Colchester’s population again began to grow and by the 1960s the construction of Route 2 led to Colchester’s new role as a bedroom community for surrounding urban areas. Though many of the original immigrant families continued to run egg and dairy farms into the 1970s and 1980s, suburban development, prompted by easy access to Route 2, began to impact agri-business. Farmland gave way to housing developments as financially distressed farmers sold their property. Legislation to rescue Connecticut farms from distress was established in 1978 by the Department of Agriculture’s Farmland Preservation Program. The program purchased the development rights to prime farmland, keeping it in agriculture production.

With a development boom in Colchester in the 1980s again threatening existing farmlands. Additional legislation, passed in 1981, provided Connecticut farmers with the Right to Farm Law. This law was created to limit the circumstances under which agricultural operations could be subject to lawsuits often resulting from conflict between suburban residents and adjacent agri-business.

In 2007 the Town of Colchester received a grant to conduct a Survey of Farms in Colchester, Connecticut. Farms in the survey ranged from 18 acres to 200 acres, with the median size 40 acres. The survey revealed insight into the lives of local farmers: “About the farmers and their families: Nearly all of the Colchester farmers in this study come from a farming background, some of them tracing their family farm connections back for several generations. Nearly all of the 8 farmers themselves have been farming for decades. Some of the farmers regard the beginnings of their own farmer status as their birth because they had farm chores as children and were aware of the family as a farming family from their earliest days. The average number of years in farming was 34.”

About half of the farmers participating in the survey worked a full-time job away from home, working on the farm in their spare time or until their retirement. The other half of the group were full-time farmers.

“Farmers generally rise very early to begin their work, and those who work at a job elsewhere, work well into the evening. Even the crops that may seem to a non-farmer to be self-sustaining, such as Christmas trees, require year-round labor, such as pruning and clearing out storm damage, to keep them going. Unlike earlier times when many children were needed on the farm, today’s farm families are much smaller. In this study, the average number of people per residence on the farms was 2.56, but some families had older children who had their own homes elsewhere; the general range for the total number of children in families was from 1 to 4. Though the children usually helped on the farm while growing up, only a few farmers receive help from their adult children now. As a result of this and the difficulty in finding affordable labor, Colchester farmers try to keep their farms and the products of their farms on a scale that they and their spouses can manage alone, with some occasional outside help.” Two-thirds of the farmers surveyed did not expect that their children would take over the farm.

Surveyed farmers products “shows the breadth of items for which there is a local market, including numerous vegetables and fruits, eggs, beef, fire wood, Christmas trees, hay, and many types of animals, including horses for equestrian activities.” “There are also foods made from the produce of town farms, such as cheese, wine, and jams.”

Renewed interest in local farm products has grown since the survey in 2007. Colchester now has a thriving Farmer’s Market operating on Sundays on Colchester’s Town Green.

PLEASE TAKE JUST A MINUTE TO COMPLETE A VERY SHORT SURVEY ABOUT THIS EXHIBIT. TAKE SURVEY HERE